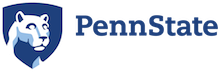

Penn State has been at the forefront of sustainable waste stream management for decades. Our food waste composting system has been a national model since the 1990s, generating some of the first high-quality public information about cost and performance and serving as a living laboratory for at least half a dozen research papers. For 15 years we have hosted the Pennsylvania Recycling Markets Center at the Penn State Harrisburg campus, which provides statewide leadership for market development and innovation. Our “Trash to Treasures” end of year move-out recovery program has served as a model for higher education across the Big Ten and beyond. And in 2014 Penn State was recognized by the National Recycling Coalition, earning the “Best of the Best” Outstanding Higher Education Award for our composting, recycling and waste diversion strategies.

Figure 1. Big Ten Diversion Rates

This is a proud legacy, but one that requires constant effort to maintain and improve. In the world of solid waste change is continuous, and in recent years that change has been swift and disruptive. This report represents Penn State’s effort to adapt to some of the rapid change already underway, but also to put in place processes and procedures for continuous improvement, so that we will be a leader in sustainable waste stream management for many years to come.

The Penn State Waste Stream

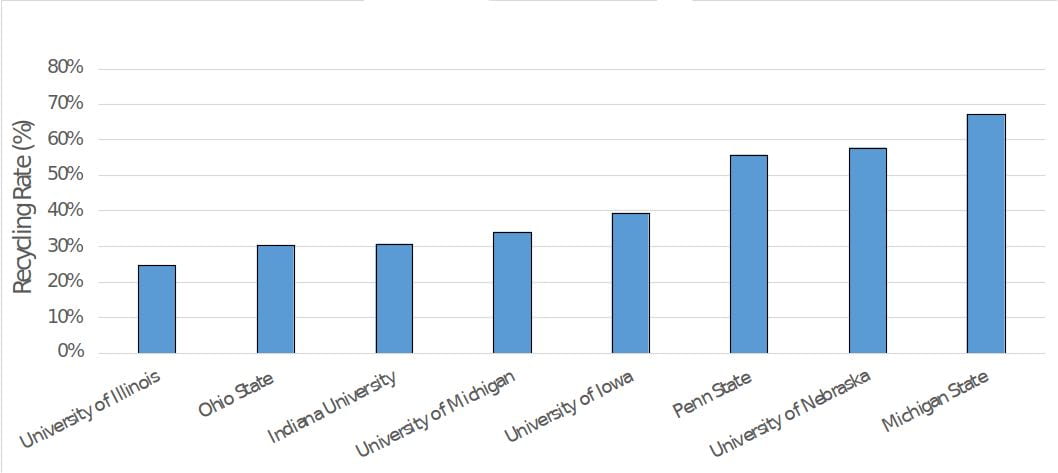

Penn State’s University Park campus generates close to 20,000 tons of solid waste each year. Of that total 62% was recovered through various recycling programs in 2017. In 2018, while the total waste stream dropped by 1460 tons (a tribute to waste reduction), the amount disposed in landfills increased by 154 tons, reducing our overall recovery rate to 58%. Data for these two years is summarized in Table 1. Components of the waste stream that are not recovered for reuse at University Park (primarily through composting) are delivered to the Centre County Recycling and Refuse Authority, which markets the recyclables and serves as a transfer station for non-recyclables destined for landfill. Tipping fees vary from $20/ton for source-separated recyclables to $70/ton for municipal waste, with a penalty for contaminated recyclables ranging from $100/ton for contamination greater than 3% to $250/ton for contamination greater than 20%.

In 2018 Penn State contracted with Kessler Consulting for a waste audit at University Park, with 12 campus buildings audited from April 16-27, 2018, and ten additional buildings audited November 5-16, 2018. Several of the tables and figures from that report are reproduced in this summary (Kessler Consulting Inc, 2019). The audit included four academic buildings, four administrative buildings, five dormitories, three dining halls, two athletic buildings, the student union (with administrative areas audited in the fall and dining areas in the spring) as well as a university apartment building and a library. The report focused on quantities, composition, and contamination.

Table 1. Penn State Waste Stream Annual Tonnages

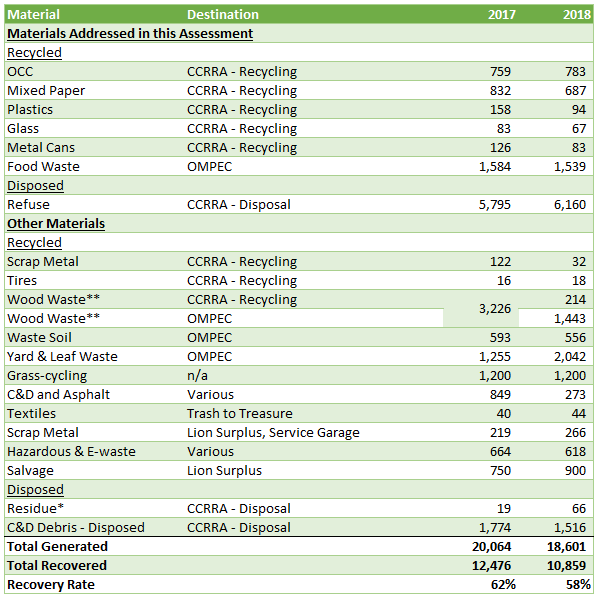

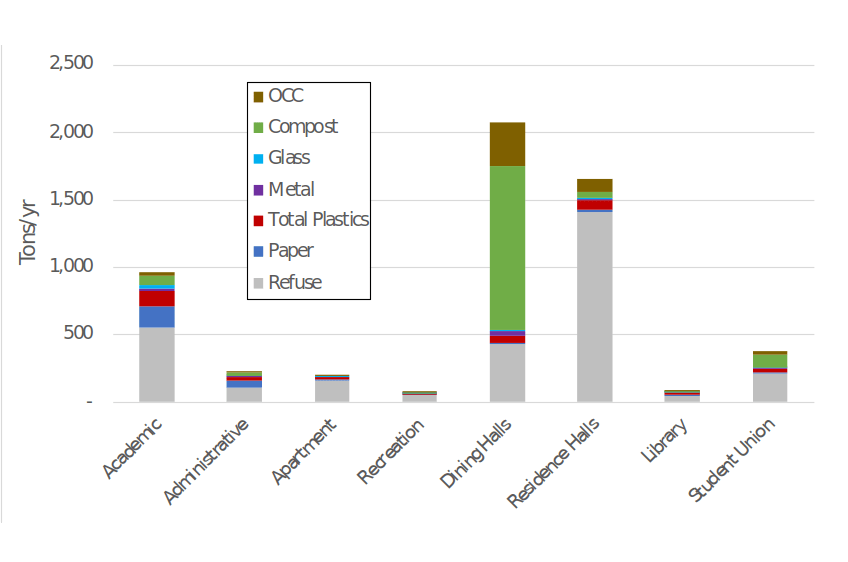

The Kessler report extrapolated from the audited buildings based on the area of similar building types at University Park to produce Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2. Estimated Campus-Level Generation for Audited Building Types

The different building types had significantly different recycling rates and purity for each waste stream component, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3 below.

Figure 2. Estimated University Park Campus-Level Generation for Audited Building Types

Figure 3. University Park Waste Stream Components, Quantities and Purity.

Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3 illustrate several important points. First, the dining halls are not only the largest waste stream generators, but also have the highest recycling rate (nearly 80%) and quantity (over 1,600 tons/year). Most of this recoverable material is compostable, then cardboard is next. Academic and administrative buildings including the library and student union have intermediate recycling rates, ranging from 42 to 52%. Dorms, apartments, and athletic buildings have lower recycling rates, ranging from 15% to 27%, with nearly half of the total University Park refuse generated in the dorms. Dorms also were estimated to have the highest percentage and quantity (tons/year) of non-recycled paper, old corrugated cardboard (OCC), plastics, metal, glass, and food waste (Kessler Consulting, 2019). Importantly, these low recycling rates appear to be correlated with low levels of contamination, indicating that while many in these buildings are not recycling those that are, are paying close attention. Purity rates are among the highest for dorms, dining halls, and athletic buildings across all waste stream components.

Values and Principles

Penn State’s solid waste management system is at the same time very visible, with bins in nearly every hallway on campus, and also invisible, because the sources and sinks of the vast majority of the materials flow “beyond the bin” are generally hidden from view. One of the goals of sustainability in general, and this Task Force in particular, is to make the invisible visible, and therefore to encourage better decisions. For solid waste, those decisions are not just about recycling and disposal, but about the purchases and processes that occur much earlier in the material cycle. There are several values and principles that guided the Solid Waste Task Force in its deliberations and informed the recommendations in this report.

Values that guide sustainable material decisions

-

- “Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.” Pennsylvania Constitution, Article 1, Section 27

- Penn State has an obligation to recycle under state law, section 1509 of Act 101. Our goal is not only complying with these requirements at all locations but exceeding our legal obligation.

- “Climate change is recognized worldwide as one of the most important issues of our time, and Penn State will be a leader in addressing and solving this challenge.” (Penn State Strategic Plan, 2016 – 2025)

- To protect both our campus community and those exposed to our waste and recyclables, materials toxicity and risks to human health should be reduced or eliminated.

- Penn State’s waste stream will be managed in ways that protect water quality and environmental health.

- “We recognize that the Earth’s resources are finite and it is our ethical responsibility to use renewable resources that can be sustained in perpetuity, using life cycle assessments and other science-based evidence to guide our decisions.” (Materials Management in Oregon, 2050 Vision and Framework for Action. p. 3)

- Penn State’s materials management systems support the university’s primary missions of education, research, and outreach. Engaging students and faculty in planning, evaluation, and demonstration of the effectiveness and efficiency of systems offers an opportunity to enhance education and research, to leverage our university as a living laboratory, and through outreach and extension to serve important needs across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Principles behind recommendations

-

- Selected waste management strategies must significantly reduce waste, be practical to implement, and be cost effective. The decision process must balance a wide range of objectives, including the values described above and the affordability and quality of a college education.

- Penn State will provide our community with information and services to guide responsible material use.

- This Task Force Report is a response to the current situation, but waste stream options are dynamic in constant flux. Ongoing institutional processes are needed for sustainable materials management decision making across all sectors, from initial purchasing decisions to end-of-life.